Mars to the Victorians

When I first embarked upon writing The Dandelion Farmer, I decided I wanted to make set it in an alternate past, rather than simply tinker with the historical narrative, and I wanted to create my own sand pit to play in while wanting to keep as close to Steampunk’s Victorian inspirations as possible.

That led me to look at the kind of alternative worlds that 19th-century authors had created. And there was really only one candidate; Mars.

The Red Planet has, and still does, loom large in the minds of so many Science Fiction authors; from Huge MacColl to Kim Stanley Robinson, and so many others. So, I set about researching Mars, not so much the Mars that we accept today, but the Mars of Victorian Fiction, but in doing so I found myself drawn down a red sandy rabbit hole into the world of another Mars – the Mars of Schiaparelli, Secchi, Lowell and Camille Flammarion, not authors but renowned astronomers and scientists, and then further beyond rationality into mysticism and the Mars of Smith, Denton and, of course, Tesla.

I learnt that, beyond the creativity of the literary geniuses, there were many different often unique versions of Mars. Believed as real, taught as fact, accepted by the scientific establishment, yet all no more ‘real’ to us today than Burrough’s Barsoom.

Interestingly, as these men were the most eminent and learned scientists and astronomers of their day, so what does that teach us about science today?

Below is a brief overview of some of the interesting things and people I discovered in my research...

Mars in the 19thc Mind Set

The Mars of 19th century science was a very different place than the Mars of science today.

Mars of the 19th c in the minds of both the Scientific community and the general public was inhabited by an array of exotic creatures and civilisations – often far ahead of ours technologically.

This was the Mars explored by the astronomers and scientist of the day. These were not wackos and outsiders, these were, men of great standing in the Scientific community who dedicated their lives to this research. This was the foundation of their contemporary scientific view of what was really going on on that strange red planet so far away and yet so near.

This was a Mars of canals wider than the Amazon, vast oceans and immense sweeping forests.

The men of God and Science

If life, intelligent or otherwise, were to be found on Mars then life on Earth would not be unique. The scientific, theological and cultural outcomes of such a discovery could be stupendous.

It is fitting, therefore, that the late-Victorian saga of life on Mars had one of its origins in the Vatican observatory. In 1859, Fr Angelo Secchi, director of the observatory, observed markings on the surface of Mars which he described as “canali,” channels. That fateful word had been launched on its career, although there was little immediate development from Secchi’s work.

Emmanuel Liais, was a French astronomer who spent much of his life in Brazil, as Director of the observatory of Rio de Janeiro. In 1860, he suggested that the dark regions on Mars, instead of being oceans and seas, as was widely believed at the time, might be tracts of vegetation. The summer meltwater from the poles, he believed, was irrigating the soil at lower latitudes and causing the dormant plant life there to rejuvenate and spread.

In 1867, the great astronomy populariser, Richard A. Proctor, published a map of Mars that gave hard, defined edges to features that had, so far, been softly rendered. Suddenly appearing as seas, islands and inlets, they carried the names of astronomical heroes.

Proctor confidently wrote of “land and water, mountain and valley, clouds and sunshine, rain and ice, and snow, rivers and lakes, ocean current and wind current" that, surely, were serving the needs of Martian life.

1877 brought a banner year for Mars watchers because the planet moved into “opposition"—the interplanetary event when Mars, Earth, and the Sun all line up and the distance between the Earth and Mars is the shortest.

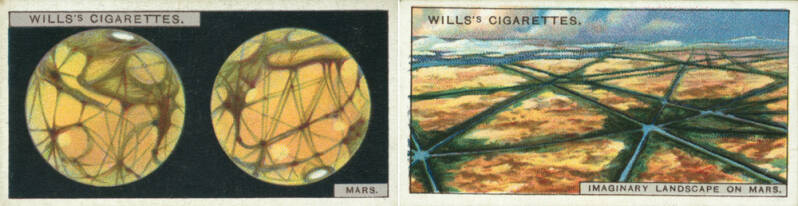

Advances in telescope technology accompanied the lucky opposition, allowing Giovanni Schiaparelli and his colleagues to complete their close-up observations and incite an enduring kind of Mars fever.

That same year, on August 17, the American astronomer Asaph Hall confirmed the existence of Mars's moons, naming them Deimos and Phobos, or Fear and Terror, after the mythical sons of Ares, the Greek god of war, Mars' alter-ego in.

Giovanni Virginio Schiaparelli 1835 –1910, was an Italian astronomer and science historian.

In his initial observations, he named the “seas" and “continents" of Mars. During the planet's “Great Opposition", he observed a dense network of linear structures on the surface of Mars which he called “canali" in Italian, meaning “channels" but the term was mistranslated into English as “canals".

While the term “canals" indicates an artificial construction, the term “channels" denotes that the observed features were natural configurations of the planetary surface. From the incorrect translation into the term “canals", various assumptions were made about life on Mars; as these assumptions were popularized, the “canals" of Mars became famous, giving rise to waves of hypotheses, speculation, and folklore about the possibility of intelligent life on Mars, the Martians.

In his book Life on Mars, Schiaparelli wrote: “Rather than true channels in a form familiar to us, we must imagine depressions in the soil that are not very deep, extended in a straight direction for thousands of miles, over a width of 100, 200 kilometres and maybe more. I have already pointed out that, in the absence of rain on Mars, these channels are probably the main mechanism by which the water (and with it organic life) can spread on the dry surface of the planet."

Among the most fervent supporters of the artificial-canal hypothesis was the American astronomer Percival Lowell, who spent much of his life trying to prove the existence of intelligent life on the red planet.

Percival Lawrence Lowell 1855 to 1916, was an American businessman, author, mathematician, and astronomer who fuelled speculation that there were canals on Mars.

He founded the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona and formed the beginning of the effort that led to the discovery of Pluto 14 years after his death.

For the next fifteen years he studied Mars extensively and made intricate drawings of the surface markings as he perceived them.

Lowell published his views in three books: Mars (1895), Mars and Its Canals (1906), and Mars As the Abode of Life (1908). With these writings, Lowell more than anyone else popularized the long-held belief that these markings showed that Mars sustained intelligent life forms.

His works include a detailed description of what he termed the 'non-natural features' of the planet's surface, including especially a full account of the 'canals,' single and double; the 'oases,' as he termed the dark spots at their intersections; and the varying visibility of both, depending partly on the Martian seasons.

He wrote plausibly about the Martian atmosphere and the means by which the canals distributed water from Mars’ polar caps to irrigate the planet before evaporation returned moisture to the poles. This hydraulic cycle appealed to popular evolutionism which perceived Mars as an old, dying world trying to avert its fate by rational and cyclopean engineering – this was, after all, an age of great canals: Panama, Dortmund-Ems, Manchester, Corinth.

For him they were proof that the Martians were not just intelligent, but even smarter than we Earthlings.

“A mind of no mean order would seem to have presided over the system we see—a mind certainly of considerably more comprehensiveness than that which presides over the various department of our own public works," Lowell wrote.

While this idea excited the public, some in the astronomical community was sceptical. Many astronomers could not see these markings, and few believed that they were as extensive as Lowell claimed.

As a result, Lowell and his observatory were largely ostracized.

After Lowell's death in 1916, astronomers developed a consensus against the canal hypothesis, but the popular concept of Martian canals excavated by intelligent Martians remained in the public mind for the first half of the 20th century, and inspired a corpus of works of classic science fiction (which we shall discuss later).

Nicolas Camille Flammarion (1842 1925) was a French astronomer and author.

Camille, a contemporary of Schiaparelli, extensively researched the so-called “canals" during the 1880s and 1890s. Like Lowell, he thought the “canals" were artificial in nature and most likely the “rectification of old rivers aimed at the general distribution of water to the surface of the continents." He assumed the planet was in an advanced stage of its habitability, and the canals were the product of an intelligent species attempting to survive on a dying world.

Flammarion approached spiritualism, psychical research and reincarnation from the viewpoint of the scientific method, writing,

“It is by the scientific method alone that we may make progress in the search for truth. Religious belief must not take the place of impartial analysis. We must be constantly on our guard against illusions." He was very close to the French author Allan Kardec, who founded Spiritualism.

(More of that later.)

An 1898 article in The Atlantic Monthly summing up the findings of Schiaparelli, Lowell, and others, noted that Mars might be in

“an advanced stage of evolution compared to Earth, at a later stage in its lifespan as a planet. Might this theory also have lent credence to the idea that Mars was hospitable to life, if not at present than perhaps millions of years ago?”

Though other contemporary voices may have decanted from their view, between them, Proctor, Schiaparelli, Lowell and Flammarion, and their adherents, caught the popular attention and imagination of the world.

Speculation thus was not about whether life existed on Mars, nor if there were civilizations there, it was about the nature of that life and those civilizations. And how we would contact them.

Talking to the Martians

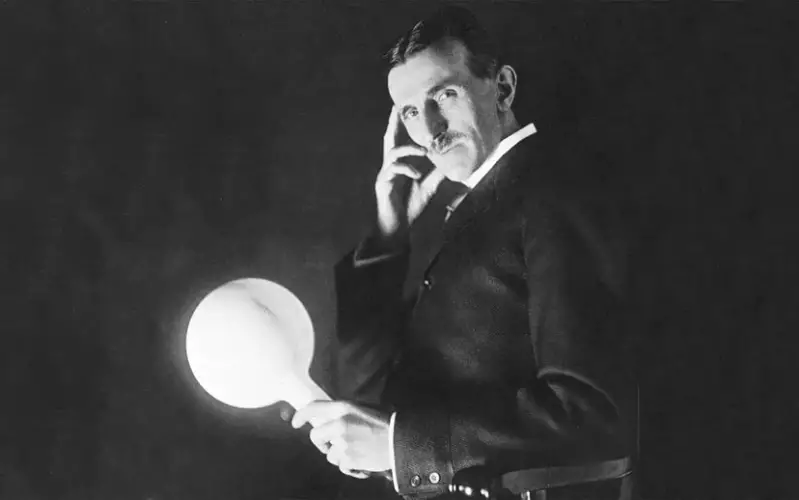

In 1904 Tesla announced he had received broadcast messages from another planet in our solar system. In his opinion probably Mars. But the signals were so ‘feeble’ that he needed to go back to the drawing board to re-think is technology.

(What he may have actually detected were pulsar signals, which would, if he'd known, been yet another great discovery to his name)

In 1921 Marconi said he believed he had interrupted signals originating from Mars (in Morse code, no less).

Others though had found more esoteric methods of communication with the Martians.

The Mystics of Mars

William Denton (1823-83), originally from Darlington, County Durham, settled in Ohio, where he became a geologist and political activist, advocating women’s rights, the abolition of slavery and temperance.

He and his family also practiced ‘psychometry’, a form of divination that purports to discern the nature and history of objects merely by handling them. Between 1863 and 1874 William and his wife Elizabeth wrote the three volumes of The Soul of Things which included reports of trips that several family members had made to Mars while in a trance state.

Together they found several more-or-less human races (each member encountered a somewhat different species), all with civilisations broadly similar to the terrestrial one.

Anne Denton Cridge, William’s sister, reported a dense life-sustaining atmosphere, great mountains and lush valleys that were home to large crocodile-like reptiles.

Hélène Smith (real name Catherine-Elise Müller, 1861 to 1929) was a famous late-19th century French medium. She was known as “the Muse of Automatic Writing" by the Surrealists, who viewed Smith as evidence of the power of the surreal, and a symbol of surrealist knowledge.[1]

Late in life, Smith claimed to communicate with Martians, and to be a reincarnation of a Hindu princess and Marie Antoinette. In 1900, Smith became famous with the publication of Des Indes à la Planete Mars (From “India to the Planet Mars") by Théodore Flournoy, Professor of Psychology at the University of Geneva.

The medium and the psychologist remained very close until 1899, when “Des Indes à la planète Mars" was first published. The book documented her various series of experiences in terms of romantic cycles: the "Martian" cycle, “Ultramartian" cycle, “Hindu", “Oriental", and “Royal" cycles.

Hélène Smith (or Helen Smith in the English edition, real name Catherine-Elise Müller; Flournoy adopted the pseudonym to protect her identity) came from a respectable Geneva family and worked as a secretary. She was also a well-known medium who gave seances to a circle of friends.

She would enter a trance state in which she spoke in the persona of spirits she encountered, and produce automatic writing and drawings. During a trance she would recall previous lives, mostly under the tutelage of ‘Leopold’, a spirit guide. Most of Mlle Smith’s previous lives were terrestrial (and included an Indian princess; hence the title of Flournoy’s book).

However, one sequence involved communication with Mars. Amazingly she produced an entire Martian language, complete with script, vocabulary and grammar, and also drawings of the Martian scenes she witnessed. The language was later discovered to be a version of her native French with some other bits added in, but it had been produced entirely automatically.

Flournoy thought Smith entirely sincere but did not believe her experiences were real. He describes them as products of cryptomnesia and as a ‘romance of the subliminal imagination’. Mlle Smith considered Flournoy’s scepticism a betrayal and ended cooperation when the book was published.

While Hélène Smith is well-documented, little is known of Sara Weiss other than that she was the American author of two books reporting astral journeys to Mars (or Ento in the Martian tongue): Journeys to the Planet Mars (1903), and Decimon Huydas: A Romance of Mars (1906).18 Both journeys were made with the assistance of spirit guides.

Her principal guide was one Carl De L’Ester but others included such luminaries as Giordano Bruno and Alexander von Humboldt. The journeys had occurred during 1893–94 though the books were not published until a decade later.

The first book, Journeys, is a rambling, digressive travelogue with detours into spiritualist doctrine. There are sections on the Martian language and flora and several well-executed drawings of the latter. Decimon Huydasis similar but has a narrative, relating a domestic tragedy that had occurred a few hundred years earlier. Both books are informed by a contemporary understanding of Mars. Giant irrigation projects, embankments and other civil engineering projects are mentioned and there are explicit references to Schiaparelli and Flammarion.

Hugh Mansfield Robinson. Was also a psychic and medium; his first astral visit to Mars was in 1918.

His Mars was home to an advanced civilisation and on his first visit he arrived at a radio station. The Martians had a highly developed radio technology and generated hydro-electric power using waterfalls in the mountains and canals. The Martians themselves were 6–8 feet tall, with oriental features and large ears. Robinson’s guide was the Lady Oomaruru, who later turned out to be a reincarnation of Cleopatra!

The idea of astral communication with Martians or astral travel to the planet was not unusual in proto-science fiction of the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

If this all has started to sound like the CIA’s Stargate Project, 1978 to 1995 (no, not the TV show) then it is worth noting that they too tried to project into Mars, at least once, “Mars Exploration: May 22, 1984.” with some very interesting results.

To the people of the mid and late 19th century Mars was a living thriving sister to Earth. A place of wonder, with complex civilisations spanning vast continents and oceans. A world home to a technologically advanced, possibly more advanced than us, peaceful people who build wonderous engineering projects to bring life to the harsh desert.

They were our friends, waiting just out of reach, but trying to contact us. Maybe to help us, to guide us or maybe to warn us of perils to come. We were not alone, the Martians were real and they were our neighbours and friends.

19thc Astronomical

science becomes fiction

It was to that point authors, like Hugh MacColl Mr. Stranger's Sealed Packet, in 1889, started writing their science fiction adventures. The short novel deals with a journey to Mars in a flying machine and describes the history and customs of the Martians, depicting a scientifically advanced utopian society.

Across the Zodiac: The Story of a Wrecked Record (1880) is a science fiction novel by Percy Greg, who has been credited as an originator of the sword and planet subgenre of science fiction. The book details the creation and use of apergy, a form of anti-gravitational energy, and details a flight to Mars in 1830. The planet is inhabited by diminutive beings; they are convinced that life does not exist elsewhere than on their world, and refuse to believe that the unnamed narrator is actually from Earth. (They think he is an unusually tall Martian from some remote place on their planet.) The book's narrator names his spacecraft the Astronaut, the first recorded use of the word. The book contains what was probably the first alien language in any work of fiction. His space ship design also featured a small garden, an early prediction of hydroponics.

The best-remembered of these stories is undoubtedly Edgar Rice Burroughs A Princess of Mars, first published in 1912, and its many sequels. In the first story the hero astrally projects himself to Mars basically by force of will and strength of desire. There he finds a vaguely Lowellian desert world, criss-crossed by canals and inhabited by various advanced (and not so advanced) civilisations.

George du Maurier (1834–96) The Martian is largely a conventional story that tells a fictionalised version of its author’s own career. However, towards the end it is unexpectedly revealed that throughout his life the author has been unwittingly directed by a telepathic Martian.

She had arrived on Earth about a hundred years earlier in a meteor shower and in the interim had tutored several earthlings. Latterly some of the Martians have taken an interest in directing suitably inclined earthlings towards an interest in and appreciation of higher things: aesthetics, philosophy etc.

Du Maurier’s Mars is an aged world that is nearing the end of the period during which it can support life. The amphibious seal-like Martians live near the equator, the only part of the planet still habitable.

Richard Ganthony’s A Message from Mars (1899) was a popular and widely-performed play. Though it was first performed in 1899 the earliest reference to a printed version appears to be a revision from 1923. Ganthony, collaborating with the novelist Mabel Knowles, later adapted it into a novel.

The story concerns one Horace Parker, the ‘most selfish man on earth’. He is visited by a messenger from Mars, who has come to show him the error of his ways, rather in the manner of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. The visitor has considerable psychic powers.

Finally To Mars via the Moon (1911) by Mark Wicks is an early space adventure. The narrator designs and builds a spaceship, the Areonal, in which he and two companions travel to Mars. The book was partly intended as an introduction to astronomy for younger readers and early chapters present astronomically-accurate descriptions of the Sun, Moon and Mars. Once the explorers arrive on Mars its geography is entirely Lowellian; indeed the book is dedicated to Lowell. The Martian civilisation is also similarly Lowellian: peaceful and technologically and spiritually advanced, with all the usual attributes of a literary utopia. So far, there has been no connection with spiritualism, but it turns out that the Martians, or at least some of them, are reincarnated earth-humans, and the narrator meets his dead son.

However, the astronomical descriptions and familiarity with Lowell’s ideas clearly demonstrate a sound general knowledge of astronomy and the dedication and preface make it clear that he was familiar with Lowell’s books.

And, of course, the greatest enemy that mankind faced in literature during the late 19th century came from that forbidding red planet; H.G. Wells' Martian invaders from the War of the Worlds. A prophetic wake up call to British Imperialism.

Out gunned and out matched technologically by a implacable unrelenting foe even the mighty British Empire can not resist them.

Edited by Mat McCall

from numerous articles

A great place to start if you want to read further is Imagining Mars by Robert Crossley

(https://www.amazon.co.uk/Imagining-Mars-Literary-Classics-Hardcover/dp/0819569275)

and a great source of modern pseudo-science about Mars is The Martians by Nick Redfern. (https://www.amazon.co.uk/Martians-Evidence-Life-Red-Planet/dp/1632651769)

Create Your Own Website With Webador